July 2004

Contents

Unearthing the Atheist Roots of Judeo-Christianity

I am a former Mormon. I was raised all my life in an active Mormon family, went on a mission and was married in the Idaho Falls Temple and had fully convince myself that it was the ‘true religion’ as is constantly drilled into the Mormon mind. But in my mid-thirties reality came face to face with belief and forced me to be more objective about my life and belief system. My experience since then with other former Mormons has taught me that the point at which a Mormon leaves his religion is probably the point at which the ‘believer’ finally agrees with him or herself to be objective because once over that hump it’s almost certain that leaving is the inevitable result because Mormonism in my experience does not hold up to objective scrutiny.

My leaving Mormonism took an unusual path. A few years prior to leaving I became interested in parts of the Old Testament from a literary perspective. In particular I became interested in what appeared to be repeating patterns of metaphors and word relationships that seemed to have as a basis a strange unidentified paradigm of some sort that seemed unrelated to both Judaism and Christianity. This so intrigued me that I took on the personal challenge of putting my finger on just what exactly was on the minds of these ancient authors when they wove into their writings some of the strange things they wrote. When I eventually left Mormonism some years later for unrelated reasons, soon followed by Christianity, my interest in identifying their underlying paradigm continued. Early on while still a Mormon I realized that I’d be in a better position to piece together what exactly was on their minds if I became acquainted with the original language the text was written in – Hebrew. Once I did the pieces began coming together, not rapidly by any means, but little by little over a period of ten years. One of the key aspects of the strange pattern that seemed to have no explanation in Judeo-Christianity was their consistent use of plant metaphors when writing of what they called mashiyach, in English translated as Messiah. For example:

“And in that day there shall be a root of Jesse, which shall stand for an ensign of the people..” (Isa 11:10)

“For he shall grow up before him as a tender plant, and as a root out of a dry ground…” (Isa 53:2)

“Behold, the days come, saith the Lord, that I will raise unto David a righteous Branch, and a King shall reign and prosper, and shall execute judgment and justice in the earth.” (Jer 23:5)

That use of plant metaphors as an absolute fundamental aspect of their paradigm and not mere peripheral adornment was realized when I discovered the likely Hebrew meaning of one of the most often repeated names in the Old Testament – God. In Hebrew the word is spelled from right to left with the letters Aleph, Lamed, Hay, Yowd, Mem, and taken at face value are pronounced as elaheem:

At around 600 BC vowel markings in the form of small dots and dashes were introduced to the Hebrew alphabet that forced the pronunciation as eloheem, but prior to the use of vowel markings the above pronunciation is more natural as there is no ‘oh‘ sounding letter in the spelling of the word.

This is an interesting word because the English translation as God has virtually no basis other than tradition. For example, although it’s widely accepted that the above Hebrew word is plural, it is translated as the singular word, God. But if a Hebrew were to read the word for the first time, completely unfamiliar with its theistic use, most likely he or she would think it means ‘oak trees‘. Yes, oak trees! This is because the first three letters spell the Hebrew word elah that is most often translated as ‘oak‘. When the Yowd and Mem letters (making the eem or im sound) are appended to the end of a Hebrew word it makes the word plural, such as cherub and seraph becoming the plural cherubim and seraphim, as well as elah becoming elaheem.

Although it may seem strange for the Hebrews to represent God as oak trees, that it was their intent is supported by a verse near the end of the opening chapter of Genesis where it says:

“So God created man in his own image, in the image of God created he him; male and female created he them.“

Substituting what appears to be the Hebrew intent it reads as:

“So [oak trees] created man in his own image, in the image of [oak trees] created he him; male and female created he them.“

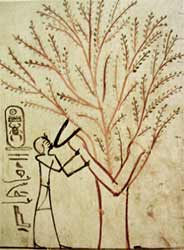

It seems odd to me that the passage as it appears in Genesis implies that the image of God is both male and female when God, according to my Judeo-Christian upbringing, was a male deity. Substituting oak trees only seemed to make the passage more bizarre. However, it began to make sense when I stumbled onto the realization that while most tree species have either male for female flowers on them, requiring both genders in a forest for the species to propagate, the oak tree is one of the few that has both male and female flowers on the same tree. Therefore, the human species is collectively an organism with both male and female members and is therefore reasonably described as in the image and likeness of the oak tree, also possessing both male and female members–a beautiful metaphor in my opinion! Another piece of the puzzle I later discovered that further supported the plant-God relationship was the realization that in Ancient Egypt, where the Hebrews are believed to have lived for a time, it was not uncommon for various sects to worship trees as a deity. For example, the picture below shows an Egyptian worshiping the god Nut represented as a tree.

Although the information I had found was enlightening it was still unclear why the Hebrews placed so much significance on plants. It wasn’t until some years later that it began making sense when I discovered an emerging science called memetics that deals with how information gets spread from person to person. Among the proponents of memetics the virus is generally accepted as a good metaphor for understanding how information spreads through various verbal and nonverbal means, such as books, symbols, lectures, art, social chat, music, body language, etc. While the virus has been the most popular metaphor for talking about memes (units of information), creating books such as Virus of the Mind and Thought Contagion, some have recognized its limitations. For example, Susan Blackmore, one of the recognized gurus of memetics, when speaking of the limitations stated in her book The Meme Machine that “the terminology of memetics is in a mess and needs sorting out.” As I acquainted myself with memetics, having the Hebrew plant metaphor problem tucked away in the back of my mind, it occurred to me one day that the plant and seed are a better cognitive tool for understanding information propagation than is the virus — in fact it’s quite an elegant metaphor. Just as plants are unable to propagate unless they alternate from plant to seed to plant to seed forms, information is unable to propagate unless it alternates from mental to physical to mental to physical forms. For example, the information in my mind that is the subject of this article remains in my mind until I transform it into a physical form such as the words and images on this page. They are like information seeds that remain in this dormant physical form until they come in contact with your mind and are transformed back into a mental form as thoughts in your mind. And once in your mind the information can also go to seed when you write or speak about these concepts with the intent of passing the information on to others. Coming to this realization was like discovering the Rosetta Stone! From that point on the fundamental paradigm of the Hebrew authors that for years both intrigued and eluded me quickly emerged from the fog into a logical and reasonable form, making their writings not only more intelligible but often nothing short of ingenious in form and meaning.

To make a long story short due to the limited space in this summary, the ‘Rosetta Stone’ revealed that the only so called god the original Hebrew authors recognized appears to be what science today describes as the very real yet intangible forces of mind and consciousness. This hypothesis appears to explain such Hebrew names as, Immanuel, a Hebrew phrase literally meaning god within us, similar to the New Testament statement, “The Kingdom of God is within you.” The paradigm also appears to be the basis for the name Israel, Hebrew for “he rules as god.” Evidence suggests that the name Israel was never intended as a reference to the Hebrew people as is generally thought today but to the consciousness that they recognized as living within them collectively through the information they shared. This appears to be the reason why the Hebrew people themselves are often referred to by a name that denotes them as the physical home for the consciousness — the House of Israel. It also appears to be the basis for the often-used name Lord of Hosts consisting of the Hebrew words yahweh mistranslated as Lord but literally means to exist. The second word, hosts, comes from the Hebrew tsabah, reasonably translated as a body or host of people. The name therefore literally means something like, that which exists within a body of people. The paradigm also seems to be behind the Parable of the Sower in the New Testament where words are represented as seeds and appears to be the basis for the Parable of the Wheat and the Tares, representing desirable information as wheat and unhealthy information such as fads and especially unhealthy religious concepts as tares (weeds).

What does all this lead to? It appears that to the Hebrew the theist notion of an external god in a distant heaven was anathema and worshipping such a god was in their way of thinking the worst of sins due its destructive influence on any culture. One of my favorite chastisements of the proponents of theism is found among the writings of the author of Isaiah in the first chapter. After verbally raking over the coals the religious leaders of his day and their vain assemblies and meaningless religious ceremonies he writes:

“Your hands are covered with blood. Wash yourselves, make yourselves clean; Remove the evil of your deeds from my sight. Cease to do evil, Learn to do good; Seek justice, Reprove the ruthless, Defend the orphan, Plead for the widow.”

A similar chastisement I also like is found in the 58th chapter where their ceremonial fast days are condemned, concluding with:

“Is this not the fast which I choose, To loosen the bonds of wickedness, To undo the bands of the yoke, And to let the oppressed go free And break every yoke?” Is it not to divide your bread with the hungry And bring the homeless poor into the house; When you see the naked, to cover him?”

Perhaps these long deceased authors possessed a wisdom the world in general lacks today, as history is full of examples of theism’s negative contribution to (and often the cause of) most conflicts, oppression and abuses in the world.

While this summary can only provide a sketchy introduction to the subject, I presented a more complete overview to the Humanists of Utah on June 10, 2004, with specifics on how information propagates like plants, including a number of examples of Hebrew words and word relationships. A subset of the same information was presented previously to the Utah chapter of the American Atheists in the Fall of 2003.

–Jeffery Ricks

Can a Humanist be a Political Conservative?

Richard Layton’s Discussion Group Report

Roy Speckhart, director of membership programs of the American Humanist Association, says a case can be made that Humanists can’t be political conservatives. He points out that less than 3% of AHA members consider themselves conservative and less than 1% define themselves as libertarian.

The political positions held by the progressive majority come directly from core humanist principles. Political conservatives aren’t merely people who subscribe to one or two conservative positions; they are those who follow conservatism as a general rule. Merriam Webster defines liberal as “favoring proposals for reform, open to new ideas for progress, and tolerant of the ideas and behavior of others; broad-minded.” The dictionary definition says conservatism “favors traditional views and values; tending to oppose change.”

Speckhart puts forth the following as probably defining positions of conservatives:

- Abortion is wrong and should be outlawed in almost all circumstances in order to protect the sanctity of life.

- The United States has been a godly nation since its founding and the government should actively make sure it stays that way.

- Homosexuality is unnatural, so there’s no reason to grant gays and lesbians the same rights and benefits as heterosexuals.

- What is good for business is also necessarily good for the United States and its people.

- Men and women, like other definable groups, have dissimilar aptitudes, which is probably why males are so successful in this society.

- Retribution is an acceptable motive for punishment of crime and for becoming involved in global conflict.

While the AHA has issued dozens of position statements that strongly oppose the outlined conservative viewpoints, no solitary position truly bars one from being a humanist. But, Speckhart suggests, “…someone who agrees with all the base conservative statements might do well to consider a different philosophical home–because humanism simply isn’t compatible with such a set of positions. Conservative viewpoints go counter to the principles outlined in Humanist Manifesto III, a document signed in 2003 by leaders of every humanist organizationin the United States and most worldwide. This is because humanists base their ideas and actions on the scientific method, compassion, and equality, not dogma and outdated convention.”

Three core principles underlie humanism’s progressive outlook: the scientific method, compassion, and egalitarianism.

Our unflagging dedication to the scientific method is relied upon because experience has proven it is reliable. Because of this approach, humanists tend to reject failed doctrines, simplistic or uselessly abstract concepts of right and wrong and stereotyped or conspiratorial notions of good and evil.

“Humanists,” contends Speckhart, “are often skeptical of unproven claims–frequently exposing falsehoods from get-rich-quick schemes to medical quackery.” They “are also generally skeptical of large concentrations of power, be they religious, governmental, or economic.” They are among the first to raise concerns about government’s suspension of liberties, government secrecy, private profiteering, and similar encroachments. Their willingness to question a wide range of authorities is contrary to those forms of conservatism which side with corporatism.

The second core principle is compassion because benefiting society maximizes individual happiness and raises the potential of humanity. Indeed, for humanists the primary purpose of the scientific method is to pursue compassionate goals, improving the world through their quest for knowledge and using that knowledge to benefit society and the environment. They are almost alone in contemporary society in recognizing that only reason, observation, and experience provide truly reliable tools for realizing compassionate ends. It is completely contrary to the principles of humanism to reject altruism as a legitimate moral force and instead, after the fashion of objectivists and libertarians, embrace a monolithic rational selfishness. Humanists are driven to embrace social policies that are inclusive, spread the benefits of wealth, diffuse social and political empowerment, and promote reasonable levels of self-determination. This is the source of the humanist embrace of democracy and individual, social, and human rights.

The third principle is the conviction that humans are basically equal and that each person should be treated as having inherent worth. Acceptance of group inequality is insupportable through humanist reasoning. Humanists recognize the ethical responsibility of individuals and society to treat each other equally with respect to social, political and economic rights and privileges. This orientation discounts many arguments against gay marriage. The commitment to compassion dictates that discrimination against same-sex commitments isn’t only an unsupported position but is morally wrong. Another example is the humanist view of the role of women in society. Despite the refusal of conservatives to give up the idea that a woman’s place is in the home, science has failed to demonstrate any significant differences in the intellectual aptitudes of men and women.

“It is obvious,” argues Speckhart, “that the core principles of humanism support liberal ideals. So it isn’t surprising that over 90% of humanists support reproductive rights, assisted suicide, and uncensored freedom of speech–an extraordinary level of agreement.” “Nonetheless, humanists must continue to welcome diverse views. Not only is this liberal open-mindedness characteristic of humanism, it is necessary for any group that so relies on disagreement and discourse to further its philosophy.” And there is plenty of room for disagreement on methods for achieving progressive goals.

In the last two years, much more frequently than in years past, the AHA has spoken publicly on social justice issues–and has watched membership numbers rise to a new historic high while reporters and opinion leaders begin to take notice. “If humanists refuse to address difficult subjects,” Speckhart concludes, “the resulting blandness will diminish the movement’s potential–both in terms of numbers and effectiveness.”

Rosier Future

Adapted from Humanists of Minnesota News & Views, June 04.

Here is a list of six things organized humanists may want from their organization:

- Rights protected; to be treated equally under the law.

- Organization; freethought community for respect, management of resources, leadership, money, recognition.

- Separation of Church and State; government agencies should not use their power to promote religion or specific churches to discriminate against freethinkers.

- Image by the public; preserve and protect us from disrespect, prejudice, and slander.

- Education of public about freethinkers in general and humanists in particular.

- Representation to public office.

Jerry Rauser, the author of this list, comments that this list can be considered long-term objectives for organized humanism. He further states that humanist chapters should provide their membership with newsletters, membership meetings, social events, chances to speak and be heard, and educational materials.

Religious Wars

Robert B. Reich, Brandeis University Professor, charges evangelicals are mounting a vigorous campaign to impose their narrow religious values on our nation and to dominate the U.S. culture. He sees their campaign to abolish partial birth abortions, repeal Roe vs. Wade and put religion back in public schools as a clear and present danger to religious liberty in our nation.

Writing in a recent issue (vol. 14 no. 11) of The American Prospect magazine, the Secretary of Labor during the Clinton administration, points out that for more than 300 years the liberal tradition has sought to free people from the tyranny of religious doctrines that today’s evangelicals are seeking to impose with a state sponsored religion.

Reich calls on liberals to recognize this ongoing assault on religious liberty. He urges a political campaign to alert Americans to the dangers evangelicals pose and hold them responsible for attempting to require teaching creationism in our public schools, demanding school prayers and opposing sex education. He cautions liberals to remind voters that however important religion is to our spiritual lives there is no room for religious liberty in a theocracy.

–Flo Wineriter